You, the coach.

A coach designs a program with your goals and individual needs in mind, monitors your recovery & fatigue to make adjustments, and always has your long term health & success at the forefront of their mind. A coach applies the latest research and best practices from the field to ensure the best possible training outcome, while continually tweaking and fine tuning based on what’s working and what isn’t. The very nature of this “subtle science and exact art” is to be continually improved upon yet never truly mastered, just like training itself. A good coach has devoted themselves not only to developing these skills, but also to applying them without bias (or at least with conscious awareness of bias). Indeed, even for those well learned in human physiology and training principles, a key advantages of working with a coach is that he/she can apply their knowledge and utilize their full skillset without being hampered by things like athlete bias or ego. A great coach is able to do these things and toss aside their own egos as well, as all too often we see coaches beholden to poor practices because it’s the way they’ve always done things, or their methods worked for someone else and/or at a different time. Coaching yourself (and doing it well) involves peeling back multiple layers of bias and ego that could blind you from making the most productive choices, not to mention the challenges of self-accountability. The pursuit of mastery is tough with a guide, but even tougher without one.

Ultimately, when training on your own, success revolves not around your abilities as an athlete, but as a coach; being able to evaluate a training log with clarity, write and execute today’s workout without fear or ego, and plan future training with the right balance of ambitious progression and cautious realism. With this in mind, if you do want to coach yourself, you’ll need to equip yourself with certain fundamental skills (like movement proficiency) and a knowledge of program design. The purpose of this brief guide is get you started with a few key principles to think about when writing your own program and progressing your workouts, as well as define some common terms that coaches like to throw around so that you can continue your education with a solid base. By no means is it all-encompassing, definitive, or even correct.

Goal Setting & Addressing Limiting Factors

If you’ve ever sat down with a trainer or worked with a coach, you’ve likely heard a variation of the following. “So, what brings you in today?”. As a personal trainer, I can’t count how many times I’ve asked a question like that, but I have rarely gotten an insightful answer right away. “Well, I want to get in shape”. Great, so does everyone else! What does that mean to you? Why is it important to you now? It takes some digging to get to the roots. Some people like the concept of the “5 Whys”, or asking “Why?” repeatedly until you’ve reached the deepest level of motivation. This is certainly a useful exercise, but it takes just as much work to figure out the right type of workout program for someone - one that fits their goals, their personality, their preferences, etc.

If you already know what you want to train for, great! If you want to get “in shape” but aren’t familiar with all of the different ways to do it, don’t despair. While you may want to “choose a path” and dial in your training objectives in the future, the nature of being a beginner means that just about anything will work initially - i.e. even cardio is likely to help build some strength, strength training is likely to improve your cardiovascular health, and virtually any movement can help with weight management and calorie balance; the key is to find something that you enjoy, stick to the basics, and become a master of consistency.

When it comes to some of the most common goals I hear about - losing body fat, looking “toned”, feeling strong and confident, longevity, etc, there are all kinds of people that fit the bill. There’s runners who are shredded, physique competitors with great cardio health and mobility, and non-athlete fitness enthusiasts who could give any athlete a run for their money on the treadmill or in the weight room. There’s a million ways to get in amazing shape, whether you want to be an “athlete”, have a “sport”, or just enjoy some workouts that prepare you for life and your favorite hobbies. Again, the most effective workout program is one that you will enjoy, not feel bound to.

By that same token, there are certain fundamentals that any human, really, should be able to do: the ability to get out of a chair (squat), get up off the floor or climb stairs (lunges, step ups), or pick things up off the ground (deadlift), etc. We call these the primal movement patterns (often called fundamental or foundational movements) and they are the categories movements you should pretty much always be doing in a well balanced training program. More specifically, they are push, pull, squat, lunge, hinge, twist, and gait (running/walking). The details of your program will vary depending on your goals, but you will generally focus on moving in the way that your body evolved to move.

Certain types of goals may prioritize certain movement patterns more than another. For example, in the sport of powerlifting, you squat, hinge, and push, but don’t do nearly as much of the other things. And that’s okay, to a point. Naturally, the more you specialize in one thing, the worse you’re going to be at others. “Imbalances”, like an excess of pushing strength in the absence of pulling strength, can lead to increased injury risk, poor posture, or other problems. Similarly, an obsessive pursuit of strength in the absence of cardiovascular conditioning can lead to health consequences (as can the opposite problem). That said, the human body is amazingly resilient and has an astounding capacity to get freakishly good at things without falling apart and can survive substantial abuse and neglect. It’s really a matter of trade-offs. Are you willing to “give up” certain aspects of fitness to have more of others, or do you want to specialize less for more “well rounded” fitness”? There’s an expression that a “jack of all trades is a master of none” and there’s certainly truth to that statement, but one need not look further than sports like decathlon, Crossfit, and OCR to know that incredible levels of concurrent speed, endurance, strength, power, and skill are certainly possible.

When it comes to assessing strengths and weaknesses, there’s two levels at which to evaluate them. First, how do your current fitness qualities compare to where they “should be” for your desired level of sport performance? Next, how do your current fitness qualities compare to where they “should be” for your desired level of general health and function? For example, if we’re looking to determine strengths and weaknesses for a powerlifting athlete, we may find that his shoulder mobility is more than adequate for a healthy bench press, but it can’t cope with the swimming he likes to do on the weekends. It’s not a sport-specific weakness, but it is a functional weakness unique to him and his lifestyle. Some might call this a “holistic” approach, others might simply say, “stop swimming!” In any case, I believe programming for a sport or goal without considering how the program interacts with all lifestyle inputs (not just other training) is woefully suboptimal.

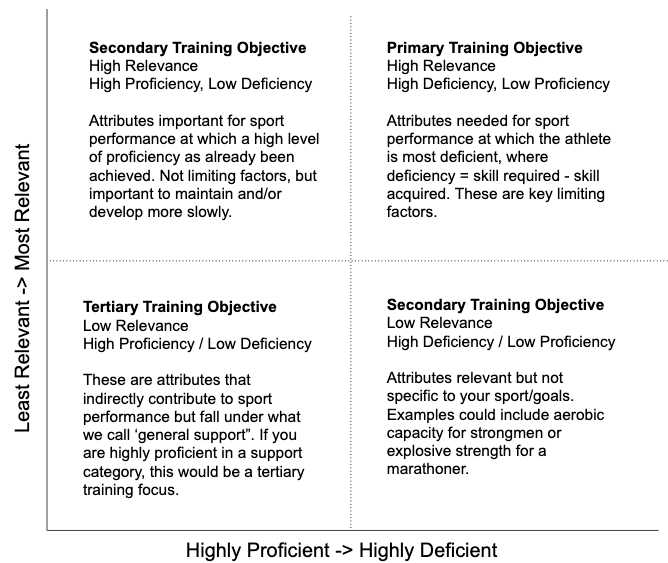

With that approach in mind, my favorite model for analyzing strengths & weaknesses allows for a systematic elimination of limiting factors of performance. First, we determine what factors are most relevant to the athlete’s performance and what factors are least relevant (but not worthless). Very few qualities will be judged as completely worthless - even internal rotation of the shoulder can have implications for proper hip extension in running gait! However, we must have a systematic way of knowing what our priorities should be. It’s not enough, though, to simply understand what attributes are important without knowing where your current abilities are compared to your “standard” - the necessary amount of each attribute needed to reach your goal. I define this as your relative proficiency/deficiency. Fitness attributes that are both highly relevant and significant weak points should, of course, be primary training goals. Other attributes should also be addressed with varying levels of focus. The simple chart below shows how you could apply this reasoning with a two-tiered approach, though you can also try a more nuanced three-tiered approach or other more complicated schemes. The main point is that you consider both how directly the skill/quality transfers to the goal and how much more/less of that attribute you actually need.

I find that writing these things down is a very useful exercise, as you may find that your current training is biased towards things at which you’re already proficient. In other words, this can be a reminder to not only work on what you’re good at, but to work on weak points within the context of specificity.

Once you have your limiting factors - those highly relevant attributes in which you’re most deficient, you need a plan to address them. Do you tackle one at a time, all of them at once, or just pick a few? How do you know? As a general guideline, I tend to progress from “less relevant” to “more relevant” fitness attributes while setting the length of training phases based on deficits in physical capacity or skill. More specifically, progress less relevant aspects of fitness until you have the general fitness characteristics needed to make larger strides in your specific fitness, then progress specific fitness until you have approached the limit of your general fitness and/or you need to return to general training as part of a variation strategy. I’ll address those questions in greater detail in the sections below, so for now, just hang out to those limiting factors and we’ll come back to them.

Specificity: to what end?

Let’s back up to the fundamentals of training in general - why we do it, and why it works. One of the most important principles in sport science is the SAID principle - or Specific Adaptation to Imposed Demand. It’s the idea that when we stress our body in some way, it will adapt to better withstand a similar stress in the future. Applied to sport training, it essentially becomes the principle of specificity, or the idea that you should practice what you want to get good at, making your training closely resemble your sport or your goals. While specificity remains an important guiding principle, it’s frequently misapplied by those who forget that strength & conditioning is inherently non-specific, indirect, and actually aims to maximize carryover/transfer to sport skill, not take the place of the sport itself. In other words, we should ensure that we are developing strength in the right muscle groups and joint angles, thinking about “force curves” when determining what positions to load, how much to load them, and at what speeds, but an endless pursuit of increasing specificity is counterproductive. As a runner, I’ve heard that lunges are more sport specific than squats. Yeah, sure, they are. They’re even more sport specific if you do partial range of motion for hundreds of unweighted reps in a row, alternating between legs on each rep. But if that’s your reasoning, why not just go for a run? Some degree of specificity is crucial, but it’s easy to take the principle too far.

Even if you aren’t training for a sport, this understanding is still important. For example, you may want to evaluate how “functional” a movement is based on how well it carries over to daily life tasks. Imagine that you train because you want to be strong enough to pick up your grandkids. A misapplication of the principle of specificity would be thinking that to get really good at picking up your grandkids, you should simply train by picking them up over and over again - and that would certainly have value when it comes to skill, but less so when it comes to physical capacity. Applying specificity with general carryover in mind, we would argue that doing heavy deadlifts is a potent stimulus that will elicit adaptations relevant to picking up grandkids. A more direct approach would argue for a rotational sandbag deadlift or a staggered stance deadlift, as they more closely resemble lifting an unstable load in real life. Both approaches are equally valid. Remember, the better choice is not necessarily more the specific one. Instead of evaluating the utility of an exercise based on its resemblance to your sport/life task, instead think about what adaptation you’re trying to achieve and what kind of stimulus will give it to you.

Somewhat counterintuitively, if you already spend quite a bit of time doing your “real life” tasks or practicing your sport, you may need less specificity in training, not more. At the same time, since sport specific training is generally more complex and requires a prerequisite mastery of fundamental movement patterns, beginner athletes will likely benefit more from general training than specific training. With this in mind, we have a “U curve” when it comes to the application of sport/life specific training. Beginners and advanced athletes likely benefit from more focus on general fitness characteristics, while intermediate athletes are the best candidates for a more direct application of training specificity.

Stimulus, Recovery, and Adaptation

Now, whether you’re developing skills with a very direct application of specificity or working on general fitness characteristics, the adaptations you’re seeking don’t happen overnight. Okay, maybe some of them do. The important thing to understand is that after a stimulus (say, a tough workout), your body is fatigued and damaged. Try to do the same workout again right away and your performance will have declined. On a physiological level, you have some micro-tears in your muscles, depleted fuel reserves, and a host of other after-effects from metabolic/mechanical stress. Recovery or the return to normal takes time. Now, the idea of recovery is currently in vogue, but it’s only part of the process. If the stimulus is right, you will not only return to baseline (recovery) but surpass it (adaptation). This super-compensation is what we refer to as adaptation, improvement, progress, etc. These terms are largely interchangeable, although I like the use of adaptation since it underlines the fact that improvement/progress is the sum of distinct physiological processes with specific drivers, amplifiers, and dampeners, not some automatic performance enhancement resulting from any form of practice. In fact, it’s possible that by training too hard or too frequently, you are able to fully recover (and feel normal again) but never actually get better. The big challenge in athletic development is getting the stimulus “just right” to allow for recovery and adaptation. Too much and you may still recover but not adapt. More than that and your performance will decline.

Since we’re on the topic, the idea of certain benchmarks like Minimum EFfective Volume (MEV), Maximum Adaptive Volume (MAV), and Maximum Recoverable Volume (MRV) have become popular, so I’ll use them here. What’s important to understand is that these are general concepts, not truly quantifiable concrete metrics. For example, I could argue that my MRV for running is about 80 miles per week - more than that, and I can’t recover. However, if I slowed my pace down, it could likely be more. If I’m also doing a lot of speed work, it’s likely to be less. These points will shift along with other stressors and can be very tough to pin down outside of very specific contexts. As a general rule, aim to stay between MEV and MRV at any given time to ensure your training is effective but not too much. In a lot of ways, that much has always been obvious and the entire concept of MEV/MAV/MRV seems too nebulous to be of any utility. However, if you take a systematic approach to establishing what these values are for yourself in specific contexts, it can be a useful way to guide your training progressions.

Let’s go back to the stimulus - your body is fatigued, damaged, etc. It takes time to recover and even a little bit more time to adapt. Having an understanding of this timescale is crucial for optimizing your training program. If you apply a stimulus again too soon, you’ll have done so before proper recovery and adaptation can occur. Wait too long, and you’ve missed opportunities for improvement (best case) or worse, allowed your fitness to backslide by “recovering” for far too long.

How long does it take to recover and adapt to a stimulus? Since even a very basic training session, say, one exercise for 3 sets of 10, stresses a variety of body systems - metabolic stress (aerobic and anaerobic), mechanical stress (muscles, bones, connective tissue), neural stress, etc, the recovery and adaptation process is not clean cut. For example, the muscles may recover at a faster rate than the connective tissue. The rate of recovery for each of these systems is also highly individual depending on a multitude of factors, so it’s tough to really pin down and provide concrete guidelines. What’s important to remember is this: more work = more recovery. Here, I mean a more scientific definition of work (force x distance). Let’s take a really tall, strong deadlifter for example - larger muscles can produce more force, and his height means he’s pulling a greater distance on each rep. That’s a lot of work! Looking at an opposite example, a small female athlete doing lateral raises is working comparatively, much smaller muscles and not do nearly as much work. It stands to reason then, that a heavyweight athlete is going to need a lot more recovery time between heavy lower body sessions than a female physique competitor will need between upper body sessions. Looking at these extremes, you’ll generally find that the SRA curve (time it takes from the stimulus until you should probably train again) is between 1-5 days for most workouts, with 2-3 days being pretty common. It’s important to remember that not all aspects of your physiology will recover at the same time and it’s likely best to consider an “average” recovery/adaptation, entering your next training session almost fully recovered but realizing that 100% recovery of all bodily systems will likely mean slower progress.

Applying this concept to the average training program, you’re looking at lower body training 2x/week (give or take) and upper body training 2-4x/week depending on your goals. Don’t feel like you have to repeat your workouts on a 7-day week though! Thinking to yourself, “It’s Monday, time to bench press again” could lead to a misapplication of SRA. What if you were actually ready on Sunday? What if you are still too fatigued and should actually wait until Tuesday? If you take an intuitive approach to training frequency, your workouts might not fit as nicely into a calendar, but it can be a good strategy for some. For others, it may be impractical to cut ties with the 7 day training week. For much of the last year, I rotated through 6 workouts every 8-9 days with great success!

How does this work for cardio? The SRA curve for low intensity cardio has the potential to be quite short, say 12-24 hours, meaning that high frequency cardio training is possible, but this isn’t always true. For example, much heavier athletes (say, strength athletes going for a jog) will incur more stress and damage to connective tissue than lighter athletes and likely have a longer SRA curve. The same can be said for impact in general - low impact cardio like biking/swimming (those without an eccentric component) will have shorter SRA curves than high impact activities like running. Add additional eccentric loading from something like downhill running, running with gear/weight, or simply being heavier will all mean longer SRA curves. In practice, this means that larger/stronger athletes looking to focus on their aerobic capacity will benefit from more low impact work as it will allow for higher training frequencies than they could otherwise achieve. On the other hand, a more traditional endurance athlete can handle high impact training with much greater frequency. When you ramp up the intensity, the SRA curve will lengthen as mechanical & metabolic stress go up. In some cases, full recovery from extreme bouts of endurance could take weeks (e.g. looking at inflammatory markers in the blood like CK and CRP levels). Just like a stronger athlete will have a longer SRA curve because they can endure greater mechanical stress, more aerobically/anaerobically fit athletes will also have longer SRA curves as they can endure greater metabolic stress and because the potency of each training stimulus needs to be much higher to elicit an adaptive response. The necessary potency of a training stimulus and its impact on SRA will be revisited in the program complexity section further down!

If you take anything away from this section, it’s that recovery and adaptation take a while. For strength training, you’re looking at an ideal training frequency of 2-4x/week for each muscle group, with room for individual variation. For endurance training, aerobic work can be done very frequently with special considerations for impact and athlete size, while more fatiguing aerobic/anaerobic work is likely done with a frequency of 1-3x/week. For low intensity skill work, the short SRA curve may allow for daily practice. There is no perfect frequency, but by tuning into body cues and closely monitoring your fatigue and performance, you can find the right training frequency for you. I find that in endurance training, most people have a tendency to push hard too often at the expense of training quality. Harder but less frequent sessions are often necessary when it comes to speed/stamina work. At the same time, dividing low intensity aerobic work into smaller, higher frequency sessions often allows for improvements to general endurance with less injury risk compared to cramming a lot of volume into not enough sessions.

Managing Similar Stressors

With a general understanding of SRA, the next step is to evaluate how different training stimuli (stressors) interact with one another. For example, high intensity intervals on the spin bike will stress many of the same metabolic pathways and mechanical structures as a squat workout. With that in mind, if you plan to do both, how do you account for that when laying out your schedule or choosing a training frequency? If you were going to squat 2x/week, but now you have to add in a bike workout, how does it work?

While activities that begin to resemble one another may confer overlapping adaptations, the same logic means they also draw on the same resources & energy systems, interfering with each other’s performance by causing similar types of fatigue, local tissue damage, etc. Given this, there are two lines of reasoning that can be applied - separation or consolidation. Let’s stick with the cycling and squatting example for a while.

In a separation of stressors approach, you would view each cycling session and each squat session as distinct workouts that all needed to be separated by their respective SRA curves. This could mean something like squatting Monday, cycling Wednesday, and squatting again on Friday, giving you a 3x/week frequency and some recovery time between each session. The advantage of this approach is that by separating the sessions out, each session will probably be of higher quality since you won’t run into the issue of being fatigued from squatting while on the bike or vice versa. The disadvantage to this approach is that it reduces the frequency of each specific activity potentially causing too much time to elapse for fitness attributes with much shorter SRA curves like neuromuscular efficiency and skill development. Imagine taking this to the nth degree when trying to fit in squatting, deadlifting, cycling intervals, and hill sprints, trying to space all the sessions 2-3 days apart. You could end up with a 3 week long training cycle with over a week between deadlift sessions. You may always feel great and well recovered going to each session, but it’s going to be tough to maintain progress with those frequencies. Still, we don’t have to throw out the entire approach - there may very well be times when separating out a particular session has advantages.

In a consolidation of stressors approach, we view short cycling intervals and heavy squats to be “similar enough” to combine into a single session. This could mean doing heavy squats immediately followed by cycling sprints on Monday, then doing a similar pairing later in the week. The advantage of this approach is that it allows for a higher frequency of each stimulus while still maximizing total recovery/adaptation time from one workout to the next. The disadvantage to this approach is that the training quality of the second workout (the cycling sprints in this example) may suffer and you have to determine the optimal training order - that age old question, strength or cardio first? The total volume of each individual aspect of the workout may be a bit lower as well, doing a few less sets of squats and intervals than if you had separated the sessions.

In practice, it’s likely that a combination of the two approaches works best, of course with individual differences and different strategies used at different times depending on the training goal. However, a “worst of both worlds” approach would be a misapplication of SRA curves and a failure to recognize the stressors as similar. That would look something like this: Squatting Monday, hard bike Sprints Tuesday, squat again Wednesday, more bike sprints on Thursday. In this example, there’s been some thought given to spacing out the squat and cycling workouts, but there’s never actually any recovery for the legs. Fatigue will continue to build and it’s likely that by Thursday, your legs are so shot that you get no adaptive benefit from your cycling intervals. Whether you go with a separation or consolidation approach, you’re likely to make exceptional progress as long as you pay attention to SRA curves and analyze the similarities/differences across different training stimuli in your program.

Interference Effect

A discussion of these approaches would be incomplete without also mentioning the interference effect, commonly known as “cardio kills your gains” or more broadly, the idea that certain fitness adaptations directly compete with and work against others. Indeed, certain endurance specific adaptations directly interfere with strength adaptations and vice versa. However, certain endurance adaptations also work directly against other endurance adaptations - who knew! See, the management of the interference effect isn’t only about strength vs cardio, but about how can we maximize multiple aspects of fitness at once without stepping on our own toes. Even for a marathon runner, this is important - how can they develop fast twitch muscle endurance and a strong lactate threshold without hindering their aerobic capabilities? While there are a lot of interesting questions to explore, let’s focus on what most people think of - managing strength and cardio in a single program.

An entire article or book could be devoted to this topic (and many have been), so I’ll summarize my best practices as quickly as possible. When you look at some of the physiological processes necessary for adaptation out of context, it’s easy to arrive at the conclusion that separating strength & cardio as much as possible is the right call, as this is the best way to minimize interference on a cellular/enzymatic level - for example, the opposing effects of mTOR vs AMPK pathways is often pointed to as proof that strength and cardio should remain separate. However, this type of analysis fails to look at other interactions between stimuli, overstating the importance of some of the short term effects from training (like changes in growth hormone release from combined vs separate training) and understating the entire SRA process and how stacked/separated sessions impact overall training quality, frequency, and fatigue management.

With some key exceptions, I think the biggest mistake you could make is doing highly fatiguing cardio and then expecting to get much adaptive benefit from a heavy strength training session. While it might make sense in terms of eliciting an optimal but fleeting metabolic response, it simply doesn’t make sense in practice and could drastically increase injury risk during strength & power workouts. Best practice: either do strength training first followed immediately by cardio (back to back sessions), or separate the sessions by several hours. Any session that requires low initial fatigue and a lot of mental focus/energy to be very productive (like a lactate threshold tempo run) may best be completed on it’s own, separated substantially from other fatiguing sessions, while cardio sessions that have overlapping adaptations with certain strength workouts (like the squats vs cycling sprints example) may best be combined with a consolidation of stressors approach.

Exercise Selection & Exercise Variation

Let’s recap what we know up to this point. First, you know that you should have some kind of goals or objective behind your programming, lest you build workouts with nothing to guide your efforts. Your efforts should focus on things most relevant to your goals with an appreciation for specificity in the sense of both the general and direct carryover. You know that you need to properly space out training sessions to optimize recovery and adaptation and that recovery is not a singular or straightforward process. Finally, certain types of workouts may enhance and/or interfere with one another, so you must take care when planning out what workouts to do when, and in what order. There are other factors that can influence how to best structure a training week that are outside the scope of this guide, but planning your week/microcycle with an awareness of SRA, separation vs consolidation strategies, and an understanding of the interference effect is a excellent place to start! At this point, you’re ready to start building some workouts!

Things get tricky here. Depending on what your goals are, what your athletic background is, where you are in your competitive season (if you have one), if you have any injuries, what your preferences are, etc, your programming needs will be wildly different. What I’ll do here is take an overview of some very broad concepts while occasionally diving into a more specific example.

What type of exercises should you do?

When it comes to exercise selection, remember this: you’re not in the gym to develop the qualities you already get from your main sport. IF you’re a runner, you’re not in the gym to build endurance. Quite the opposite really. Your purpose in the gym is to develop fitness qualities that you don’t/can’t develop from running but will still be beneficial to you. A runner runs to build is engine, but an engine can’t get anywhere without the rest of the car. You’re in the gym to build the rest of the car. Likewise, if you’re a baseball player, you’re not in the gym to throw balls and swing bats - you’re in the gym to improve the health and strength of your legs, shoulders, core, etc so that you can do that other stuff better. And if you’re trying to “get in shape”, your purpose in the gym isn’t to get tired, fatigued, or work up a sweat - it’s to either build muscle, gain strength, improve balance & coordination, etc. Make sure that the exercises you choose are good choices for your training objectives. A full breakdown of different exercise types is beyond the scope of this guide, but I offer these two (seemingly conflicting) perspectives.

Don’t underestimate the power of the fundamentals. You can get in really good shape focusing on nothing more than squats, deadlifts, pushes, and pulls. These compound movements (and the barbells they’re usually performed with) have been around for a long time and have created some amazing transformations. You don’t need fancy equipment or knowledge of hundreds of exercises.

Any distinction made between corrective exercise & physical therapy, functional movement and athletic training, strength/power/hypertrophy development, and other training outcomes is needlessly rigid. With creative exercise selection and strategic modifications, it’s possible for an exercise to serve multiple purposes. You can build muscle with an exercise that also improves stability. You can perform a shoulder corrective that also integrates the rest of the kinetic chain. You need not separate a physical therapy appointment from a strength training session.

Let’s expand on this dichotomy. You can focus exclusively on bilateral barbell movements in the sagittal plane and get great results. You can devote your training exclusively to unilateral & rotational movements with uneven loads and also get great results. Others may find themselves in need of a physical therapist after years of getting beaten into the ground by heavy barbells or waste hours performing pointlessly dumb exercises that try too hard to do too many things while failing at all of them. You can make traditional exercise a lot more “restorative” with the right coaching and cueing and you can load/progress non-traditional exercises far more than their often given credit for. The point is, training is going to look different for a lot of people. If your training sticks to the basic principles of specificity, overload, SRA, and progresses intelligently over time, you’re likely to get some cool results.

My advice? Make sure you’ve picked at least 1 or 2 movements from each of the primal movement categories - squat, hinge, lunge, push, pull, and twist (we’ll leave off gait for now) - focusing on variations that are relatively simple (low skill) and easy to load/progress. From there, you may add variations of these lifts, corrective exercises, more complex movement patterns, different planes of motion, etc, but you if you don’t have a simple and easily loadable variation of each foundational lift, you’re probably missing out.

How many exercises should you do in a session?

Before tackling this question, it’s important to understand that variation - the idea of changing something about a workout, especially the exercises chosen but also the set & rep scheme, exercise order, and other details - is a potent stimulus in and of itself. Simply doing a new exercise is likely to cause more soreness, muscle damage, and usually “gains” than an exercise that you’ve been doing for months. Unfortunately, a misapplication of variation is the idea of “muscle confusion” or constantly doing different things so that avoid ever developing “adaptive resistance”. The problem here is that variation isn’t the only way to get results and an excess of variation detracts from many other important aspects of training.

Since you can stick to the same workout for several weeks/months while progressing things like load, intensity, volume, or adding/lifting certain constraints like tempo/belts/gear/etc, you need not over apply variation. With this in mind, we don’t want to do too many exercises in a single session, as we want to leave most of our tools in the toolbox so that they are ready when we need them. Do too many exercises in a workout or training program, and you won’t have any new tricks up your sleeve next time.

Variation isn’t the only factor to consider though. We also have at look at injury risk / overuse and skill acquisition. In an extreme example, if you know that you need about 10 sets of tough leg work in a given session, you could do 1 exercise for 10 sets or 10 exercises for 1 set each. Ignoring the variation problem for a bit, what are the pros and cons? In the 1 exercise example, you’re likely to get very good at that exercise, but with the risk of developing overuse injuries from repeated stress/strain on the exact same muscle fibers and connective tissue structures. In the 10 exercise example, you don’t ever get enough practice at a given exercise to develop much proficiency or skill. The chances of overuse injury are low.

Remember the U-curve of sport specificity from earlier? Turns out we have something similar with variation and exercise selection. Beginners benefit more from less variation because they need to prioritize skill acquisition. Everything about training is a new stimulus to them, so you don’t have to worry about mixing in a lot of new exercises for a while since they’ll keep getting better with minimal (if any) movement variation. They also can’t handle very much total volume, so focusing on just a few movements allows for enough practice reps at each without it being overwhelming. On the flip side, advanced athletes need a more potent stimulus in each training session and likely need to make greater use of variation as a stressor over the course of the entire program. Because they’ll be rotating exercises in/out more regularly, it’s helpful to have only a small selection of exercises in the program at any given time. Intermediate athletes, then, are likely to benefit from the greatest number of exercises in a given session. In terms of movements per body part or primal pattern, a good rule of thumb is 1-2 movements each for beginners, 2-4 for intermediates, and 2-3 for advanced athletes.

How often should I change up my routine?

Eventually, you’ll want to apply some form of variation to keep things fresh. This generally comes in the form of new exercises, set/rep ranges, or the addition/removal of certain constraints. If you are sticking to the same training goal (for example, continuing a hypertrophy phase but adding variety), you’re likely to be rotating in a few new movements. Writing a completely new program is likely not needed - simply rotating in 1-3 new exercises every 4-12 weeks should be sufficient. Beginners need less frequent variation, while intermediate and advanced athletes will usually add variety every 4-6 weeks.

If you’re working on skill development and/or a movement seems to work particularly well for you, you can leave it in the program - perhaps indefinitely, focusing on other means of progression and variation. For example, you may keep squats in your program at all time, moving from high rep squats to tempo squats to box squats to belted squats to beltless squats throughout the year. This ensures that you get really good at squats and don’t stagnate. This is one reason that you see so many variations of the bench press - powerlifters want to get good at benching but there’s only so many chest exercises out there that can develop maximal strength for benching - that’s why you have close grip bench, reverse grip bench, spoto press, paused bench, larson press, 1.5’s, bench pressing to a board, slingshot bench, benching with bands/chains, etc. In other words, within the bench press there is endlessly variety, but it’s always bench press.

Program Complexity

Remember those limiting factors? Were we going to address them all at once, in a particular order, at random? Just train hard and hope they go away? This is perhaps my favorite aspect of program design: determining what to work on, when, and in what order. When determining where I want to focus my efforts, I ask two main questions:

If my limiting factors are connected, is there an order of operations I should follow, like laying a foundation first?

Can I improve multiple things at once?

The answer to both of these questions, of course, is “it depends”. What we’re really trying to determine is what type of periodization will work best for the athlete. Periodization is essentially the idea that overall fitness may improve MORE if you address limiting factors in a particular order rather than haphazardly. For example, a simple example is that race performance was much better when a period of low intensity training preceded high intensity training compared to the reverse. Most traditional models of periodization don’t even ask question #2, assuming “no” and then immediately looking for the best possible order. However, in many cases, it is possible improve multiple aspects of fitness in a single training program. Let’s call the number of distinct training goals program complexity. A complex program aims to improve several things at once. A simple program just focuses on one. Somewhere in the middle, perhaps we’ll focus on two things at once.

To determine how many things you can simultaneously improve at, let’s return to the concepts of MEV and MRV. If we want to improve at Task A and Task B, we’ll want the volume of each to exceed their respective MEVs but not exceed our global/systemic MRV. In other words, we can’t devote all of our recovery to one goal - we need to achieve a potent enough stimulus from Task A and Task B to drive adaptation in each category, but there’s still only so much stress we can handle.

In a beginner, MEV is extremely low. It takes very little of any kind of stimulus to improve, but MRV isn’t that bad. With this in mind, a beginner can likely meet their MEV in different training goals simultaneously without exceeding global MRV. This means that in a single training cycle, the “newbie” can probably get a little bit faster, improve their endurance, build a little muscle, and drop some body fat - all in the same 6 weeks! This means that for beginners, complex programs can work really well.

With repeated exposure to certain stimuli, you build up an adaptive resistance. Running 1 mile isn’t going to cut it any more for improving your endurance, you’ve got to run 2. And 3 sets of squats won’t cut it anymore either, now you’ve got to do 5. But wait, I can’t do ALL of that. Yes, eventually the MEV needed to improve won’t be doable for multiple things at once. At this point, you’ll have to focus on just a few things (or one thing) while putting others in maintenance, then changing your emphasis later on.

In advanced athletes, they’ve been exposed to potent training stimuli for years and have very high resistance to further improvement. As such, the MEV needed to improve at even one aspect of their fitness may approach their MRV, meaning that they have to pour their heart & soul into a very specific element of their training to get any better while carefully managing/maintaining everything else. In other words, advanced athletes need simple, focused programs.

Somewhere in the middle is the intermediate athlete, who likely can handle more than one thing at a time, but not several. In this individual, we’ll usually focus on two distinct elements of fitness.

Complex Training

With complex training - training for beginners aimed at improving several aspects of fitness at once - it can be tempting to throw the kitchen sink at them without a real plan thinking - “they’re a newbie, it’ll work”. Instead, I still focus on a few key areas of fitness - ones that will set them up for success in future training cycles when they aren’t a beginner anymore. You’ll want to do a full strengths and weakness analysis to determine where special attention should be paid, but I often start with the following: Aerobic Base, Hypertrophy Support, Neuromuscular Power. By prioritizing low intensity aerobic conditioning, we ensure they have the general work capacity to handle more metabolically taxing training in the future and prepare their connective tissue for higher intensity work down the road. By focusing on hypertrophy with simple compound movements (like squats and hinges), we improve overall balance & coordination, build lean mass, and develop good movement patterns with plenty of volume/reps, all without the injury risk of heavier loads. If they demonstrate readiness and sound mechanics, adding in neuromuscular speed/power training (i.e. strides, short hill sprints, broad jumps) early on lays a foundation from which they can move to more taxing speed, power, and explosive strength training. Focusing on each of these 3 elements will likely lead to well rounded fitness developments across the board for 6-12 months. Remembering this approach can even be useful for advanced/intermediate athletes, as a fitness maintenance program may look quite similar. Within complex training, there is still progression. We may progress load/volume in the hypertrophy workouts, speed/volume of the conditioning work, or introduce more taxing speed work over time. Eventually, certain aspects of fitness will be moved to maintenance and you’ll focus on fewer things at a time.

When applying the proficiency vs relevance model from above, you may want to bias or skew a complex training program in the general direction of one’s weaknesses. For example, if the person you’re working with used to a be a runner and is still on their feet a lot, but has no strength and poor coordination, you can still apply the same multi-faceted approach but devote a larger percentage of their program to the strength side of things, possibly working on more single leg & stability exercises.

Simple / Linear Training

With linear training, there is usually a singular focus with a path laid out. For example, if you have a powerlifting meet, you may transition from hypertrophy training to strength training, with ever increasing specificity and attention paid to your competition lifts. Essentially, it’s a smooth & linear transition from sets of 10, to 5s, to 3s, to 1s (more or less). In hypertrophy training, volume will generally build linearly (or in waves) until adaptive resistance to hypertrophy necessitates a low volume strength cycle to resensitize the muscles to hypertrophic stimuli. In the case of powerlifting, hypertrophy training serves as general support while strength training is specific. In the case of hypertrophy itself, strength training serves as general support while the hypertrophy work is specific. In either case, you progress from “most general” to “most specific”, or “least relevant” to “most relevant”. Looking at your proficiency vs relevance analysis above, for linear training, I recommend moving from low to high relevance over the course of a training program, adjusting the length of each phase based on the relative proficiency/deficiency in each.

Another idea: In endurance training, you have “top down” and “bottom up” approaches. Here, you may assume that the “speed is there” and you just need to improve your endurance or vice versa. For example, you want to run a 20 minute 5k but can only hold that pace for 3 minutes right now. You have the speed and will work on doing it for longer and longer periods of time. Alternatively, you could say that you can already run a 5k, but it takes you 25 minutes. In this case, you’ll work on making that time faster and faster. While you’re unlikely to come across a program as simple as that, most linear programs work kind of like that - either approaching a goal from the “speed side” or “endurance side”. In this case, my personal experience and research shows that athletes with a stronger endurance background but less natural speed will get better results tackling an event from the endurance side, focusing on gradually increasing their speed at a given distance that they can already complete. Athletes with a speed background tend to get better results maintaining their speed by starting with shorter distances and working their way up to their goal. In practice, this means that a slow-twitch endurance dominant athlete preparing for a fast 5k might do well to including a half marathon 6-12 months out, a 10k 3-4 months out, and gradually work on getting faster as the races get shorter. A fast-twitch speed dominant athlete may do well to race a mile, then a 2 mile, then a 5k, trying to “slow down as little as possible” as their endurance improves with longer races. Now, this doesn’t invalidate the idea that low intensity training should precede high intensity training for best results - instead, this informs the progression of the high intensity workouts themselves.

Funnel Periodization

In funnel periodization, you combine the idea of top-down and bottom up approaches. Going back to the 5k example, you may start a training program focused on slow base building and fast hill sprints. Later you may race 10k’s and do 400m repeats. Later still you’ll work on mile repeats and 4-5 mile tempo runs, eventually “converging” at your 5k goal, having developed the speed and endurance side simultaneously. This approach tends to work best for intermediate athletes who can handle multiple progressions within a single training program.

Can you apply a funnel periodization model to strength training? It’s possible and I have some interesting ideas about what it could look like. I haven’t seen anything that resembles it before, but if you’re reading this and have seen something, send it my way (conjugate doesn’t count, as the two training styles don’t converge). I'll save my ideas here for a future post!

credit: The Science of Running

Progression

The saying “only brush the teeth you want to keep” comes to mind here. If you want to get better at something in a training cycle, you have to progress it. You’re not going to get better at running but doing the same workouts over and over again. You’re not going to squat 300 for sets of 10 if you’ve been doing 200 for sets of 10 for the last 8 weeks in a row. That being said, progression is subtle and can come in ways that we don’t expect.

For example

Last week, on Monday I ran 5 miles. On Tuesday I did a 5k time trial in 20:00.

This week, on Monday I ran 7 miles. On Tuesday I did a 5k time trial in 20:00.

In this example, it looks like the Monday workout was progressed by adding more volume but the Tuesday workout was stagnant. However, I would argue that both workouts progressed, as the same 5k time on Tuesday was accomplished under greater fatigue and stress in week 2 and thus was a more challenging workout and potent stimulus.

In strength training, we may not necessarily progress load or volume directly. As a matter of fact, we can progress anything we want to. For example, we may progress TUT (time under tension), decrease rest periods to progress/increase metabolic stress, or increase sessions density, performing the same sessions with a greater level of pre-fatigue. All of these are potentially valid ways of progressing a strength workout. That being said, you’ll generally want to focus your progressions on the aspects of fitness you’re trying to improve and key drivers of that specific adaptation. For example, if you’re focusing on hypertrophy, you’ll want to ensure that the things you progress from one workout to the next are actually drivers of hypertrophy - mechanical tension, proximity to failure, time under tension, metabolite build up, etc. If you progress the weight/load but don’t control for the other factors, you may be progressing strength more than hypertrophy.

Again, progress everything (eventually) while also realizing that some elements of progression are more hidden than others.

Infinite Staircase

I like to imagine training progressions like an infinite staircase. You can’t keep progressing the same thing forever, but by adding variation as a stressor while scaling back others, you can start the cycle of progression over again without backsliding. An endless progression of intensity and volume would quickly lead to outlandish and impossible workouts. However, you could keep that cycle up for a couple of weeks, change a few movements and restart the intensity/volume progression. That way, the variation serves a stimulus for further improvement and you can re-apply volume/intensity increases for gains all over again.

Some programs call for a little break between rounds of the staircase, called a “deload”, a planned period of significantly lower intensity/volume than normal training, allowing the mind/body to fully recovery and “reset” before more hard training. It’s debatable if this is truly necessary or not. If you do push hard enough for long enough that you need a deload week, I don’t doubt that you need one and should take one… but did you need to push all the way to the breaking point to begin with? A slightly more conservative program could potentially allow for a continuous cycle of variation & progression without the need for a deload. Deloads are still the popular approach but I’ve seen a lot of exceptional coaches and athletes design and improve on programs without them. In some ways, deloads allow for more mindless progression - I’ll just keep making this harder until I die, then take a break. A program without deloads would require more precise autoregulation (a topic will visit further down).

An off-season is sort of like a big deload placed within a year - a few weeks or a month of less intense training after a tough 11 months of work. Like a deload, if you need it, take it. If you have a competitive season, chances are you’ll have naturally overreached and benefit from time to unwind and truly recover. Some of the best athletes in the world take a full 2-4 weeks off from training, completely, each year, and that off-season is very well deserved. On the other hand, if you’re a recreational level athlete or are already inconsistent with your training, taking an intentional off season likely just means even more time that you’re not improving.

Maintenance

As alluded to in the periodization section, everything should be progressed, just not always at the same time. It’s not realistic to chase simultaneous improvement of dozens of fitness attributes, though juggling several may be possible at times. However, just because something is not actively being progressed does not mean it should be forgotten. This is naturally built into complex and other non-linear training models, but even when following a linear program, it’s important to keep this principle in mind.

Maintaining an aspect of fitness is far easier than improving it. This maintenance volume (MV) is often low or even zero in some cases. You can look at this in terms of an actual number of sets, reps, miles, or repeats, or you can look at in the context of a training emphasis. For example, a direct application of the MV concept would be needing to run at least 20 miles per week to maintain your aerobic fitness. An indirect but equally valid application would be that an intense strength training cycle is sufficient to maintain muscle mass even in the absence of focused hypertrophy work. When ensuring that no fitness qualities get “left behind”, think both about the amount of volume/intensity that you’re putting into directly training them and also how much indirect stimulus they get from related training.

In practice, this means that even while focusing on developing endurance, speed work should not be totally abandoned - it may be done at lower frequencies and/or “mini workouts” may be sufficient for maintenance without drastically contributing towards MRV. When comparing disparate fitness qualities like strength and endurance, the application of the interference effect suggests that progressing one while maintaining the other is wise, as only beginners are likely to make substantial gains at both within a single training cycle. By dropping endurance volume to maintenance levels, you can be sure that interference with strength development is minimal and vice versa. Completely abandoning endurance while building strength or vice versa would mean regression and thus constitute inefficient program design.

Autoregulation, autonomy, and Results analysis

In coaching, the idea of autonomy is allowing the athlete a sense of control. By doing so, not only do we see better program adherence, but we actively encourage the athlete to make “in the moment” decisions about the direction of their training based on their internal body cues - things we can poke & prod at, but never appreciate at the same level. An overly rigid program, no matter how carefully it is planned, will always be inferior to one that allows for some autoregulation - adjustments made to workout details and program progressions made by the athlete, not the coach. Even when the athlete is the coach, we can still take advantage of autoregulation to ensure we are optimizing training frequency (SRA), volume/intensity, etc. While the lines between the two are blurred, I’d argue that autoregulation represents modifications made by the athlete based on internal cues (i.e. soreness or fatigue), while programming adjustments (more broadly speaking) are made by the coach based on external feedback & results (did the load or speed improve). When coaching yourself, you have to do both.

Unfortunately, simply saying “listen to your body” is not sufficient. Sometimes my body tells me to eat a dozen donuts and I tell it to shut up. And just about everyone’s body will tell them to slow down in the middle of a time trial. We have to decipher what cues to listen to, which ones to ignore. We must develop a strong sense of kinesthetic awareness, “listen” carefully to take inventory of all that we sense, feel, and experience, then determine what these inputs potentially tell us about the state of our fitness, form, and fatigue. This is complicated by the fact that different sensations have different “meanings” in different contexts. If you’re feeling some residual fatigue going into your squat session in week 5 of a hypertrophy block….well, get over it. As long as you’re still progressing relevant metrics and stimulating growth, some residual fatigue is normal. On the other hand, if you’re feeling brutally sore going into a sprint workout, you should adjust your frequency/volume/etc.

When making program adjustments, we have to look at the results to see what’s working and what isn’t. If your goal was to improve strength in the 10-12 rep range, but after a 12 week training cycle, or squat 10RM didn’t budge, then something, somewhere, went wrong. However, it’s important to look deeply at training logs and other progress indicators to see what really happened. One of my most common experiences as a coach is something like this: “But coach, it’s been 3 months and my deadlift hasn’t changed!”. Yeah, looks like you’re still pulling the same weight. But 3 months ago you looked like a cat throwing up, now you look like someone deadlifting. Even if your target metric didn’t change, still evaluate other aspects of the fitness to see if you inadvertently (or intentionally) made improvements elsewhere, or in ways that conceal actual gains in strength, etc. If you really didn’t get the improvement you want, first double check that the training actually made sense for the goals - was it specific? Are you measuring something that ought to have improved? I’ve had athletes go “off program” and test a deadlift 1RM at the end of a hypertrophy cycle because they were feeling strong, only to be disappointed at their apparent lack of progress. Of course your 1RM didn’t get better! You haven’t pulled anything off the floor over 80% in 3 months! Instead, looking some their average weight in something like RDL for 10, we should see gains. If your training truly was specific and your tracking the right metrics, and still aren’t observing progress, you need to check your stimulus potency and evaluate adaptive resistance. The workouts might simply have been too easy or too hard. Or, perhaps there hasn’t been enough variation and you just keep throwing more miles at someone who’s been focusing on mileage increases all year - try something else.

By evaluating your results with clarity and tuning into internal body cues for game-day decisions, you can ensure that your program is constantly evolving to meet your needs and drive the most impressive results.

Further Reading

Great discussion of the principle of specificity by Jacob Tsypkin on exercisephilosophy.com

Overview of the scientific principles of strength training from JTS on youtube, including SRA and Overload.

Look at stimulus and adaptation from an endurance perspective with Steve Magness

Comprehensive discussion of concurrent training and the interference effect in the Hybrid Athlete

More talk of concurrent training on Stronger By Science

Blurring the lines between rehab and normal training with Dani LaMartina / EliteFTS

The value of accessory work (and more rehab talk) with Dani LaMartina / EliteFTS