Why Do We Move?

When someone approaches me for coaching, it’s generally because they want some guidance on how to exercise. Before we can jump in to what you should be doing, we have to back up and think about why. This is where most coaches like to explain the “why” behind an exercise or a program, but it’s usually done backwards: we often have a preconceived idea of what you’re going to do (e.g. squats & deadlifts), tweak the details, and then explain why it’s a good program for you based on the goals you have. Don’t get me wrong - this can work. After all, a solid program built on foundational movement patterns and scientific principles can be effective for anyone when scaled and personalized appropriately. However, it’s kind of like decorating a cookie cutter apartment instead of building your own custom mansion from the ground up.

Let’s go back to square one - why does anyone even bother with exercise? Wouldn’t it be great if we just didn’t need it? After all, we only cram made up sets and reps into 30-60 min time blocks to avoid the consequences of a lifestyle that’s otherwise devoid of natural movement. If you think about it, so much of our health & fitness routines revolve around compensating for 21st century comforts & conveniences while maximizing efficiency. We’ll dive deeper into that below, but we also have to recognize that modern society affords us the luxury of movement that goes beyond health, like competitive sport & recreation. In reality, people’s need and desire for exercise is messy. There’s a lot of things, good and bad, that compel people to move, but it’s important to understand why if we want to get results. This could mean unpacking the “bad” to coach behavior change and develop a healthy relationship with movement, taking a more nuanced approach to layers of multifaceted health & fitness related goals, or (most likely) both.

We have to stop organizing exercise into convenient bubbles - I’ve included a few common ones below. This myopic view of exercise is so pervasive, we often don’t realize how limiting our beliefs about exercise truly are. I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve heard someone say, “Well, I know I should run, but…” or other “I should ___” statements without truly understanding why they think they need to do that thing. With a little digging, I find that it’s usually because that’s the most normal, acceptable, or popular form of exercise for their goal. In other words, people think they need to run to do cardio, practice yoga for mobility, or train like a bodybuilder to build muscle. However, unless you’re goal is to be a professional runner, yogi, or bodybuilder, your fitness routine probably doesn’t have to fit that mold.

This view also assumes that any exercise or program can only address one goal. Think about it - we see a lot of training programs for marathons, for powerlifting, for bodybuilding, or various sports, but very few 12 week programs designed to “build a modest amount of muscle, progress general athleticism, mobility, and balance, improve motor control, skill acquisition, and executive attention, and bulletproof your shoulders from injury.” In reality, the latter is more in line with the average person’s goals, but we rarely see programs with a wide range of goals at the forefront of the design. Furthermore, many practices have trickled down from high level competition that don’t actually work so well for the general population - in other words, many folks emulate the approach of high level athletes who, in reality, have much more focused goals and are willing to make more sacrifices to their quality of life in pursuit of them.

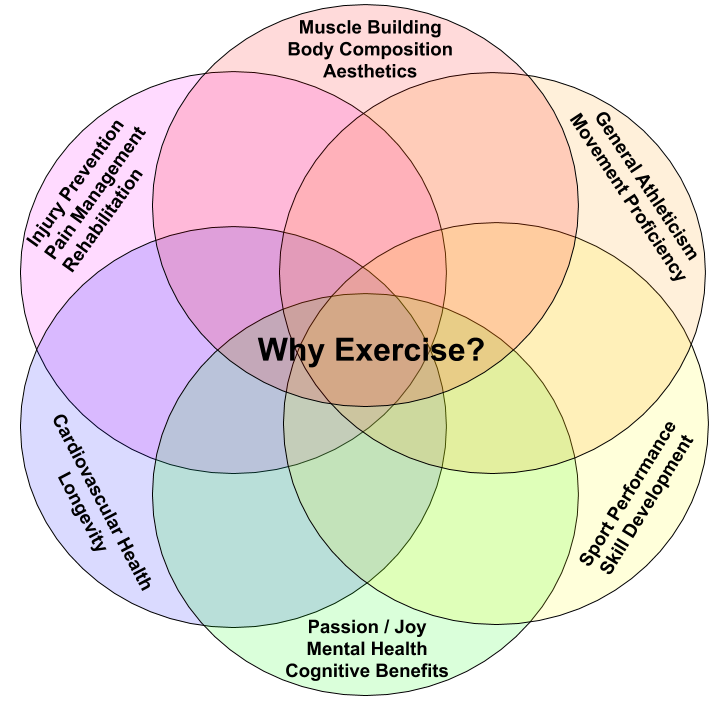

To get the most out of movement, we need a continuum based approach. A particular exercise, workout, or program need not fit a rigid definition of “strength”, “cardio”, “mobility”, etc, but can blend many elements of fitness (and wellness) together. For example, a heavy single legged deadlift performed with proper cueing may fall into the dark orange section above the “i” in “exercise”, blending elements of hypertrophy, rehab, general athleticism, and some sport specific skill development, though it likely doesn’t score very highly when it comes to cardiovascular health, longevity, or passion/joy (unless you truly LOVE single leg deadlifts like I do). Fringe movement practices like MovNat, Animal Flow, Parkour, or even training for sports like MMA, climbing, or gymnastics will all have elements that fall somewhere inside the not-technically-a-venn-diagram below. For example, performing a sit-through during a natural movement flow combines elements of rehab, cardio, and general athleticism, not to mention the cognitive benefits of learning a new skill / pattern. Depending on your specific goals, you may find that traditional exercise like “cardio” and “weights” is ideal for you, or you may find increasingly more benefit in unconventional training or movement geared directly towards a hobby/sport.

This also opens up the opportunity to investigate how to get more out of everything we do. By realizing that all training fits somewhere along a multi-dimensional continuum, we can look for ways to add additional benefits to a workout without detracting from the primary goal. This could include adjustments like maintaining an integrous shoulder position during a tricep pushdown, providing additional proprioceptive feedback during a stability drill, gamifying elements of a workout to increase cognitive engagement, or adding shoulder care exercises as “filler” between heavy lower body sets that would otherwise by passive recovery. This isn’t to suggest that we should constantly aim to “hack” our workouts to unreasonable levels of efficiency; of course, taking this concept too far can be counterproductive. However, if your adaptive threshold for a given set of stimuli is low enough that several can be applied in unison without risk, I find it best to do so. For instance, you may get sufficient stimulus for hypertrophy from a unilateral exercise despite it creating suboptimal tension when compared to its bilateral analogue. In that instance, there’s no reason to toss stability benefits aside in relentless pursuit of hypertrophy optimization if you don’t have the training history to demand it (perhaps you do, in which case, carry on). In this vein, there are endless ways that we can enhance a workout. Exploring all of them is beyond the scope of this article, but here are my top 3 tips for better workouts, that have less to do with the knitty gritty details and more to do with our overall approach.

Move More, Exercise Less

Before we even dive into the details of a workout, we have to discuss the fact that exercise is completely made up. Literally everything about it. Barbells are convenient implements designed to make lifting weights as easy as possible. When we talk about “range of motion”, it’s usually an arbitrary distance defined more by the equipment and environment than by our anatomy. Sets and reps are merely constructs that don’t actually convey a lot of biomechanical information about stress, strain, or fatigue. We usually only call something exercise if it’s done with the intent of improving fitness, yet carrying a grocery basket around the store is likely a more functional workout than many folk’s gym routines. The fact remains that we wouldn’t have to overcomplicate nutrition & exercise if we hadn’t oversimplified everything else about survival. From a health perspective, if you move often, eat when hungry, prioritize protein & produce, and have healthy social interactions / relationships, you won’t need a gym membership or exercise routine to live healthfully. As biomechanist Katy Bowman states, we treat exercise like a “movement vitamin” instead of addressing the underlying issue - a poor movement diet. Now isn’t the time for my monologue on a much needed cultural shift that emphasizes natural movement, but I will share an example about a lifestyle shift I’ve made to exercise less. Perhaps it will give you some ideas.

I don’t particularly enjoy traditional mobility work. I find stretching to be boring and time consuming. Now, you’ll often hear a pseudo-scientific argument against flexibility training like “when was the last time you saw a lion stretching”, but it also ignores the fact that you don’t see lions sitting in a chair hunched over a keyboard for 8-12 hours a day. Since I don’t want focused mobility work to be a large part of my routine, I now focus on the most ancient form of mobility training of all (far older than yoga) - sitting on the ground. As I’m typing this, I’m sitting cross legged on the ground doing some hip mobility work. I’ll occasionally shift my position, may switch to a baby cobra pose later on, or move to half kneeling at the kitchen table - the point is, by making a conscious choice to not use a conventional seating arrangement, I’m getting a lot more mobility, movement, and variety in my day than if I sat in a chair. This requires some discomfort, but if we can tolerate some discomfort and inconveniences, we’ll find it pays back dividends elsewhere. I also commute on bicycle everywhere I go, building in a lot of cardio and low intensity movement into my daily life… but that’s another conversation altogether. You’ll have to make your own calculated decisions about what changes you’re willing to make in your lifestyle to gradually chip away at your need for formal exercise. The more we’re able do to that, the more we can accomplish in our remaining time at the gym. Of course, extremely active lifestyles could potentially detract from the energy needed for more potent training stimuli in the gym, but I find this only applies to ~1% of people and is a moot point if the end goal is simply quality of life vs sport performance.

Make It Fun

Now, just because some movement is intentional and purposeful exercise doesn’t mean it can’t be fun. I actually believe this is one of the most under-appreciated aspects of training. Some people say the best fitness program is the one you’ll stick to - that’s especially relevant here, as you’re more likely to stick with something you love than something you hate. You’re also more likely to adopt a growth mindset, focusing more on the process than the outcome (and ironically achieving a better outcome as a result). This is important for true mastery, but even if you’re just looking to drop a few pounds or look better in your jeans, prioritizing fun is still massively important for your results.

Hating your workout program often results in something called “hedonic compensation” - or replacing discomfort/pain in one area with pleasure/comfort in another, subconsciously rewarding yourself for accomplishing an unpleasant task. This is why a lot of studies show that training for a marathon, on average, doesn’t confer weight loss benefits and can even lead to weight gain! It’s not that marathon training is bad for you or that distance running “makes you fat”, but if you’re suffering through an unpleasant program day after day, other aspects of your lifestyle are probably going to suffer. On the flip side, if your fitness routine is enjoyable, you won’t feel like you need a reward for it - it was worth the effort on its own. That’s why, for weight loss, it drives me crazy when people talk about how many calories something burns; I honestly couldn’t care less. Find a style of movement that you think is fun - that will always be the superior option, even if Zumba only burns half the calories of Orangetheory (I made that up, but it’s probably not far off).

Now, your movement isn’t going to be “fun” or “not fun”. Again, we have a continuum. Some days, even the most gung-ho runner won’t feel like heading out the door. Or you hate snatch grip deadlifts but your coach put them in your program. That’s okay. The point is, you’re working on something that, deep down, you care about for its own sake, not just the number on the scale or the tangible results. You also don’t have to fall in love with exercise or with movement in general; there may be aspects of your workout program that you never really like. In those cases, we can look for ways to make it “a little bit fun” but turning it into a game, doing it with friends, doing it outside where you can enjoy some fresh air, or adding your favorite tunes. In other words, don’t turn it into a sufferfest. Make it something you can look forward to (parts of it, anyway).

Practice Mindfulness

Yep, I’m talking about the same kind of mindfulness from zen meditation and buddhist tradition. In a mindful movement practice, we focus on open monitoring - an intentional awareness of any thoughts, feelings, and sensations that arise during a workout. We then use this information to make conscious adjustments that improve the quality and efficiency of our movement. This could mean creating more tension where it’s needed & less tension where it’s not, fine tuning rhythm or sequencing, or linking movement with breath more intentionally. This can be done anywhere with any movement, but movement that demands focus and eliminates distraction is ideal for developing this kind of focused attention and mindfulness. That’s why practicing novel movements outside of your normal exercise repertoire is great for recovery, stress reduction, overall athleticism, and cognitive function. By focusing solely on the task at hand, you are practicing a form of moving meditation that can be done anywhere.

One of the best ways to practice mindfulness is to step outside of your comfort zone and learn a new skill - ideally one that’s pretty tough. While low-skill training has advantages (it’s easy add load/intensity without risk), high-skill training has tremendous benefit too. When most people think of high skill training, they think of a technical sport like Olympic weight lifting. This certainly does carry some risk and it might not be your cup of tea. I like ground-based natural movement practices because they’re inherently low risk; you can safely learn challenging movements and “fail” just a few inches from the ground without worrying about a barbell crashing down on you from overhead. There’s countless good options though - and remember, finding something FUN is also key. Try mountain biking, rock climbing, yoga, or parkour, or anything else that seems fun yet challenging. If you have a “primary sport” that you train for, try exploring things that are vastly different. If you’re an avid cyclist, for example, stepping outside of your comfort zone with mountain biking might not be a big enough step for maximal benefit. As someone with a distance running and powerlifting background, learning parkour during quarantine has been an immensely eye-opening experience. I’d encourage you to look at where your current fitness routine lands on the movement diagram at the top of this article and look for gaps. What are you NOT getting from you current routine? Use that as inspiration for your next recovery session, new hobby, or something to incorporate into your regular routine moving forward.