This week’s quick hitter covers the topic of weak hips and glutes and how it affects running form. Sort of.

In a traditional running population, you see weak hips or “under active” glutes all the time. This often leads to hip drop, excessive external rotation during the recovery phase of the stride, and a host of other issues. In my coaching, I don’t exactly work with a traditional running population though. I work with a lot of runners who squat and deadlift double, sometimes even triple their own bodyweight, yet the still show some of the symptoms of weak hips and glutes in their gait analysis. How does this even make sense?

There’s two distinct possibilities here.

First possibility: It’s not about strength, it’s about activation. Or recruitment, engagement, or whatever word you want to use to describe what it means to actually maximally utilize a muscle that’s supposed to be working.

Second possibility: These symptoms / form issues can be caused by others problems unrelated to the hips.

In reality, both of the possibilities are likely working together in unison. Even athletes who can deadlift 500 pounds and have a butt made of reinforced concrete may still not be maximally utilizing their posterior chain throughout their stride. Or, something else “down the chain” in their stride is breaking down first, leading to issues up the chain at the hips despite their incredible strength. If we want to utilize these freakishly strong muscles that many lifters-turned-runners have, we need to optimize their stride from the ground up (literally).

This article on irunfar does an excellent job explaining how a properly loaded foot and lower leg create what Dr. Uhan calls a “turbo-charged hip” and the exercise he recommends to improve leg alignment in your stride. By developing strong feet, ankles, and calves, you’ll have the structural integrity and strength to maintain optimal leg positioning and actually utilize those strong glutes without your stride getting all whacky and inefficient. Dr Uhan recommends the power raise, which is essentially just a calf raise done in a specific way - slight bend in the knee, external rotation pressure and tension in the hips/glutes. This exercise is fantastic, but it’s not the only thing you can do. I recommend pairing it with single leg stability work like the hip airplane and single leg deadlifts. On their own, single leg deadlifts won’t necessarily improve your stride (most people do them horribly wrong), but if you apply the principles of the “power raise” to other posterior chain work and single leg work, you’ll definitely notice the difference.

A more nuanced possibility to consider is that problems with the hip or leg could arise from a centrally mediated neurological phenomenon - the posterior oblique sling that connects one hip to the opposite shoulder/lat through the thoracolumbar fascia. See, action at one arm/shoulder will strongly influence the action at the opposite leg and hip. You can try this simply - while running, if you think about swinging your arms faster, your stride rate will likely increase too. Or, allow your arm swing to drastically cross the midline and you’re likely to develop a crossover gait as well (how a runway model walks, but running). If you lack sufficient shoulder internal rotation, you may naturally achieve less hip internal rotation while running, thus having more hip extension and some of the problems seen here. In a desk-sitting bench-pressing population, it’s wouldn’t be surprising if some shoulder issues could trickle down to the lower body during gait.

So, the next time you are trying to figure why your hips are broken, look beyond the hip. Look at your feet. Look at your shoulders. Look at your overall posture. Look at your breathing, ribcage expansion, hip-shoulder separation, pelvic floor, etc - these all have massive implications in hip function during gait that go well beyond clamshells and hip abductions!

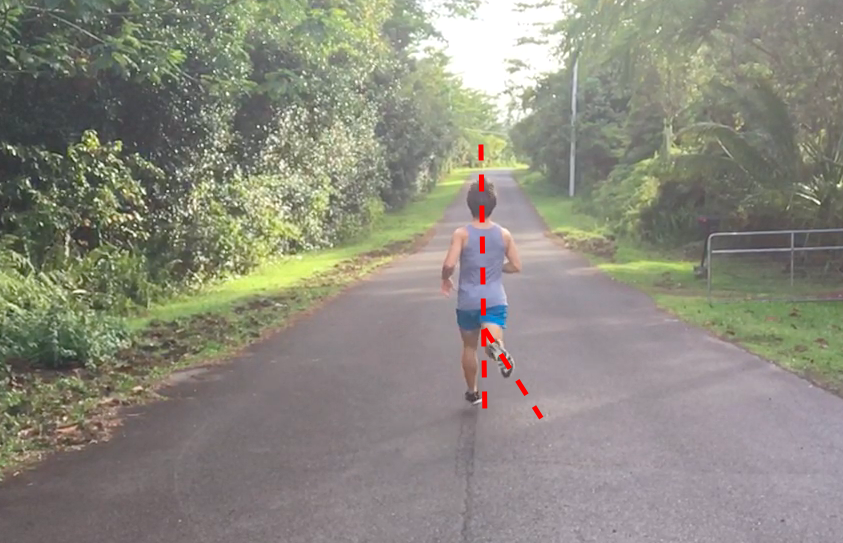

An externally rotated foot is usually associated with a lateral hip/torso shift. However, in cases where the leg alignment is off yet the glutes are incredibly strong and stable (many powerlifting runners), you’ll see this. External rotation, but no problems at the hip. Still, fixing the stride will optimize power production, even if you’re not hemorrhaging power through lateral motion.